What to Watch Verdict

Netflix's "Stowaway" is a beautifully shot space flick with the same old problems: Crisis, conscience, and consumables. There's almost nothing new here, save for the actors.

Pros

- +

🪐 Wonderfully shot for a movie with only four characters.

- +

🪐 All four actors filled their roles admirably.

Cons

- -

🪐 So many plot problems, starting with the film's title.

- -

🪐 The dilemma of ethics and morality are overshadowed by the science fiction and realities of space.

- -

🪐 The symbolism of another sacrificial Black man is really hard to swallow right now.

Three things you need to get to Mars: Oxygen, food, and water. OK, you need a lot more to get to Mars. (Like, say, advanced degrees in astrophysics, rockets, training — that sort of thing. But oxygen, food and water are the most basic of supplies.

We've seen that time after time in pretty much every space scene that finds astronauts in peril. Apollo 13 finds its astronauts in need of a makeshift CO2 scrubber to clean the oxygen. The crew of the Icarus II in the excellent 2002 Danny Boyle/Alex Garland movie Sunshine ended up with an extra crew member as they worked to restart the sun, leaving them without enough oxygen. Mark Watney needed years worth of Martian-grown spuds to make it back to Earth in The Martian. More recently, in the Netflix series Away, the multinational crew headed to the Red Planet found itself confronting crisis after crisis. Food. Oxygen. Psychological profiles that in no way were conducive to spending years locked up in a tin can.

And now we have Stowaway on Netflix.

Sometime in the future, we see three astronauts, working for a company called Hyperion, launch on a mission to Mars. Hyperion itself isn't actually important, which is good, because we don't really get any of its backstory. We don't ever actually hear or see anyone from Hyperion. Ever. The comms are all one-sided.

What is important are the three people on board. Cmdr. Marina Barnett (Toni Collette) is in charge and is the actual pilot in the trio, which can you tell by the fact that she's the only one at the controls. Every other passenger is seated behind her, just along for the ride. You get a sense of unease as they make their way out of the atmosphere and into space, with the bumps and the sounds and the danger of riding a column of fire hundreds of miles above the ground. The launch isn't without hiccups — the engines appear to be underperforming for some reason. But there's enough fuel to get to orbit and continue the mission, and so MTS-42 continues on, with the Kingfisher rocket mating with the rest of the craft that will take everyone to Mars on the two-year mission.

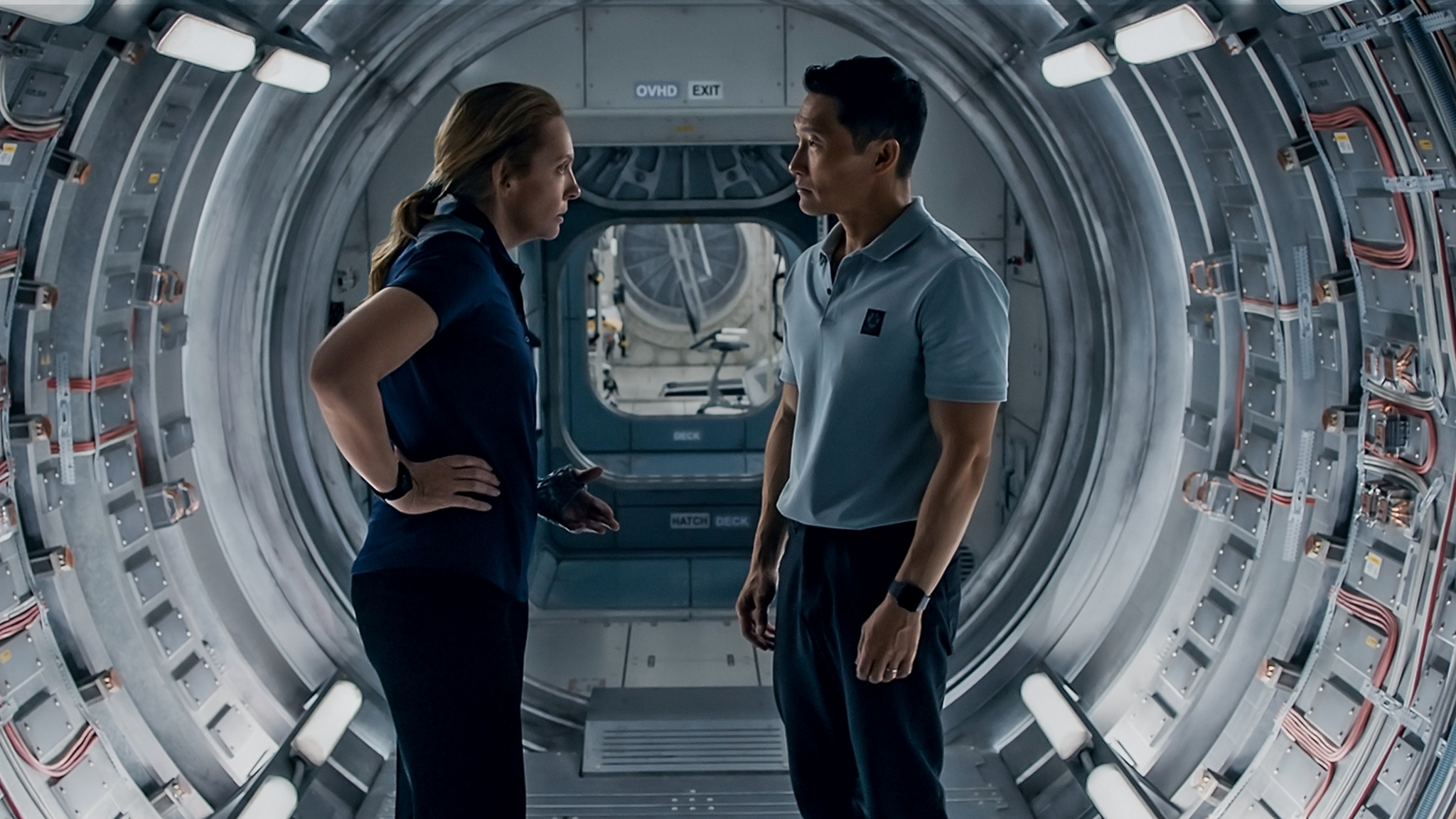

We get our first good looks at medical researcher and doctor Zoe Levenson (Anna Kendrick) and biologist David Kim (Daniel Dae Kim), as everyone does their part in unstowing gear and doing a surprising amount of grunt work. None of this stuff was prepped before everyone got to space?

That brings up an important part of Stowaway as a feature film. It's set it in space, but you'll actually get more out of it if you don't get too caught up in the sci-fi details. And that's a shame, because there's actually been some thought put into those details. Instead of just spinning its way into artificial gravity (or, worse, flipping a switch to explain it away), MTS-42 is using a "tethered gravity system" that's maybe not explained quite enough for normal audiences, but still plays a fairly integral part in the story. (If you really want to get into this sort of thing, definitely read Seveneves by Neal Stephenson, which in addition to being one hell of a story is also super heavy in physics and orbital mechanics.)

The latest updates, reviews and unmissable series to watch and more!

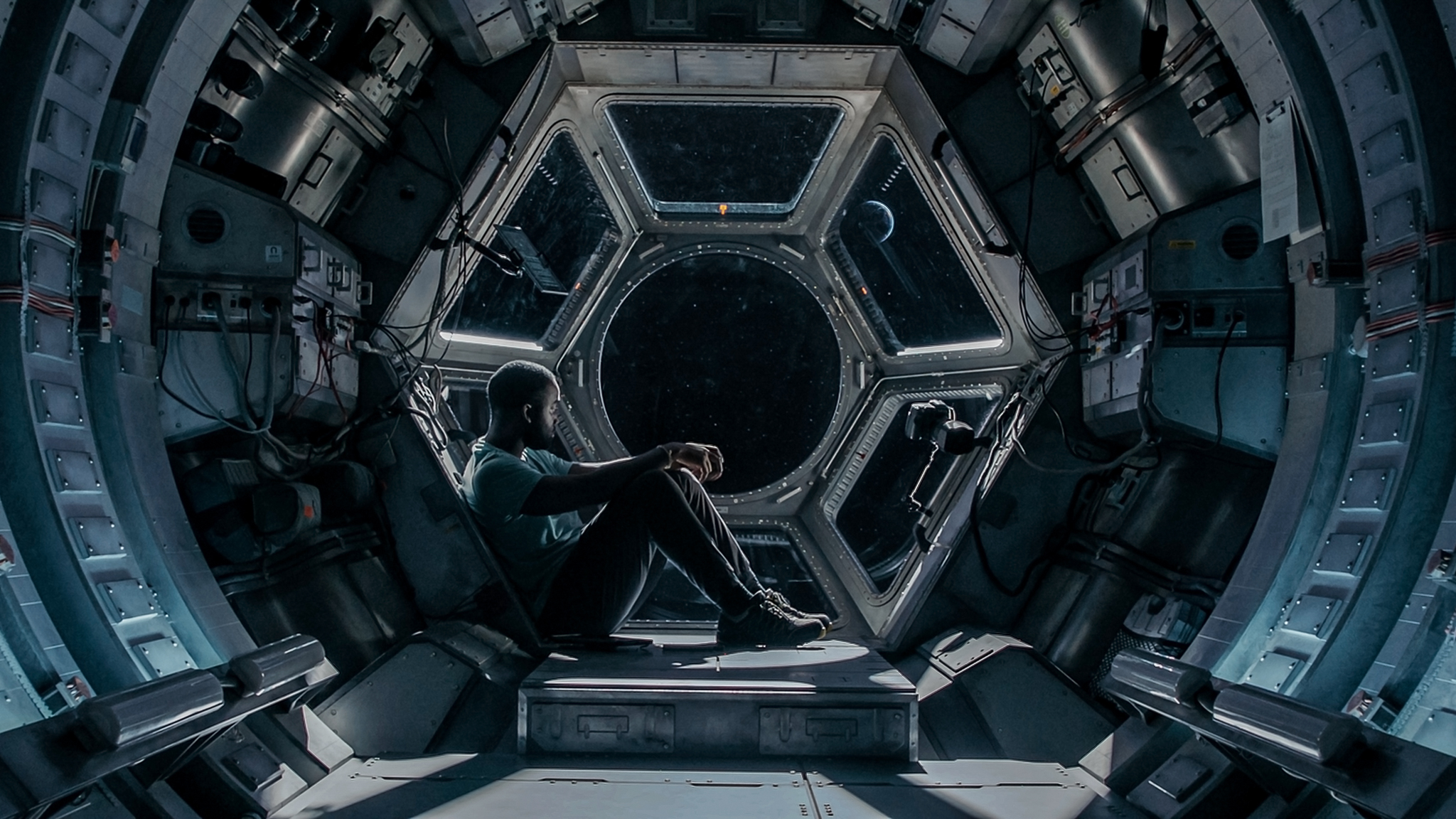

But at the same time, the whole thing comes crashing down — literally — when Barnett discovers blood dripping out of an an overhead panel. She opens it up to find launch technician Michael Adams (Shamier Anderson) trapped inside. He's unconscious and dangling by a harness. Barnett tries to catch him as best she can as he falls, and injures her arm int he process. Also broken is a pipe attached to the Carbon Dioxide Removal Assembly, which is bad. Too much carbon dioxide in the air, and you'll suffocate. That's the same problem the Apollo 13 astronauts faced, as you'll recall.

Michael is brought to the infirmary and patched up by Zoe. He eventually regains consciousness, but he has no idea how he got trapped, or why nobody managed to notice that he was missing. "We don't make mistakes like this," David says. And you have to believe that he's right. And it's not like the MTS vehicle is so large that there'd be so many people scurrying around that someone would just be missed. It's built for three people — one of whom now has a busted wing.

Michael, at first, is apoplectic. His first thought is for his younger sister — he's her legal guardian. Hyperion takes care of that, though, as you'd expect, though we're starting to question its ability to perform basic math, like "If five people prep a spacecraft for launch, and only four come out before it takes off — should we worry?" But with that concern taken care of, Michel dedicates himself to be a productive member of the crew, despite not actually being trained to do anything on the mission once the Kingfisher left the ground. He wants to be of service now that he's stuck there.

Maybe he feels bad for injuring the commander. Maybe he just wants to keep busy. But worse than a broken arm or an extra mouth to feed is that the CDRA, as it's commonly referred to in the film, is broken beyond repair. Worse than that is that apparently there is no redundancy. No secondary CDRA. Just lithium hydroxide canisters that are meant to be a backup for three people, not a primary source of CO2 removal for four.

Let's take stock: We have a spacecraft originally built for two people but was refit to barely support three (because cost is still a thing in this future world) now supporting four people. We have a redundant-less CO2 scrubber that's inoperable. Turns out that's not the real problem, because they can just vent CO2 over the side. The real problem is oxygen. There's just not enough.

All four of them are going to die before they reach Mars.

Fortunately, one of them is a biologist. And so David is tasked with scrapping the microgreens project he's begun during the transit and instead will fire up the algae project that's meant to figure out if we're able to produce oxygen on the Red Planet. But David doesn't have the right equipment — it's on Mars — and if he tries to jury-rig the algae on the ship, it could die, and then he'll be stuck on Mars without a damn thing to do.

Barnett doesn't see another way.

So David gets to work injecting green goo into collapsable water bags, and the first batch seems to work. The second batch, however, dies. Just like he feared.

All four of them are going to die before they reach Mars.

And that's where the ethics and morality part of the movie start to kick in. What if there wasn't a fourth person on the ship? Barnett didn't initially let Michael know the bad news — that his being there was going to kill everyone. Instead, she has David start his algae project. And if that doesn't work, then the'll have to get rid of Michael. David takes matters into his own hands. He's not a bad person, not by a long shot. But the logic is pretty clear, and so he raids Zoe's stash of medicine and spells things out for Michael: Either he stops breathing, or they all stop breathing.

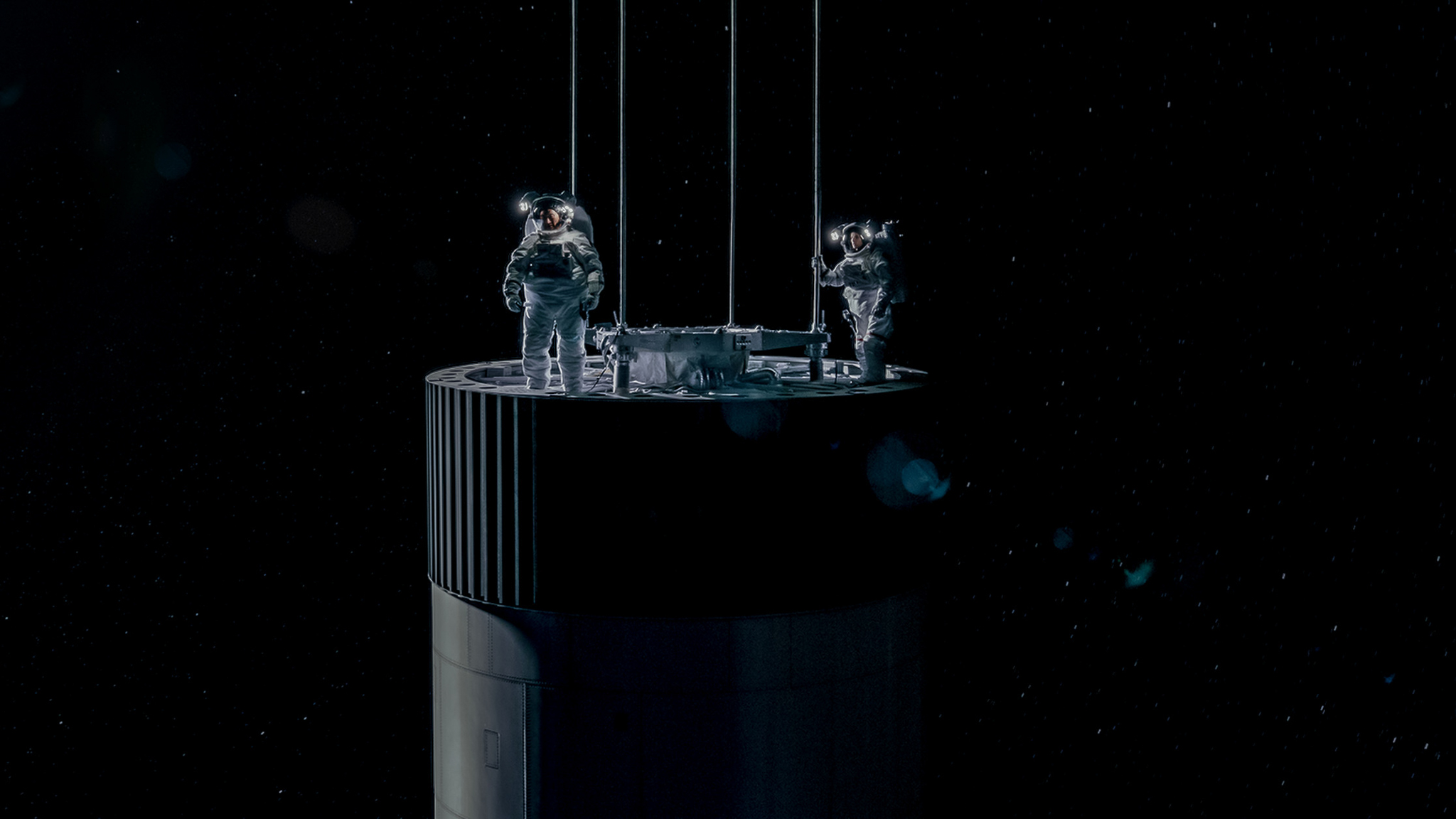

Zoe gets the ethics and morality of the whole thing but refuse to give up looking for a way to fix it that doesn't include a dead body. And she sees it — some 500 meters away, on the opposite end of the tether. Their spacecraft is on one end of the tether, and the Kingfisher — the mostly spent rocket that got them into orbit — is on the other side, with the solar array in the middle. Kingfisher still has some liquid oxygen in its tanks, and that could be use for life support. But they won't know if there's enough without getting to it, and that means climbing the tether. At the center of the tether, there's no gravity (or at least a lot less), because it's effectively not spinning. So they'll have to climb up, against gravity, then slowly slower themselves down to the Kingfisher without falling as the gravity builds again.

It's dangerous — and that's even without the worry of breaking any other parts of the ship along the way, perhaps most importantly the solar array. Zoe at first tries to teach Michael how to make the climb. But he doesn't have the training and is still injured. He's out. She thinks she's going to have a hard time persuading David to make the climb with her, but he says yes without a second thought. He's not a monster, just pragmatic.

So they make it to the Kingfisher and start to fill the first of two portable tanks with oxygen. That's when the other shoe drops, in the form of a poorly timed solar storm. They have to high-tail it back to the MTS vehicle and into the hardened module, or they'll die. They make there, just in time, but lose the one oxygen tank they managed to fill.

All four of the are going to die before they reach Mars.

There's still some liquid oxygen on the Kingfisher, though. Someone just has to go get it before the main tank — which is now leaking because they pierced it to drain it — before it runs dry. The solar storm could last hours, and they don't have that long to retrieve whatever liquid oxygen is left.

Michael says he'll go get it, sacrificing himself in the process. But he couldn't do it the first time. And, as Zoe points out, "If you don't make it back, one of us dies, too."

There are a few beats of silence, and then David calls it. "I'm willing." Zoe is right behind him. "I'll go. I can do it. ... I can't let you do this. So, make it back home. Go have a kid, and send them to Yale, OK?" (She was a Yaley, he went to Harvard, they gave each other a hard time.)

Whether or not Zoe gets the job done isn't the point. The crux of Stowaway comes with the dilemmas, the most basic of which is do you sacrifice one life to save three? And if so, whose?

But that's just a dilemma with the story. There are a number with the film itself, and mostly how it presents Michael Adams.

Websters dictionary defines a "stowaway" as "a person who hides aboard a ship or airplane in order to obtain free transportation or elude pursuers." Michael presumably was doing neither, though it's never actually explained just how the hell he got locked inside a ceiling panel in the first place. He's not a stowaway — he's an accidental passenger.

There's also the greater problem of Stowaway quite literally weighing the worth of a Black man against the worth of the rest of the crew. Yes, Michael wasn't supposed to be there, nor was he trained for the mission. His worth as a crew member is quantifiably less than that of the others. But Michael's worth as a human being is not.

It's not that nobody saw that or took it into consideration. Burnett did. David did. Zoe did. It's just that killing off the only Black character in a film is a really hard pill to swallow in 2021, and it doesn't take a feature film — whose title doesn't actually fit the reason for the conflict — and a fictional mission to Mars to confront ourselves with the decision to take a life, let alone an African-American life.

We've literally been seeing it every day, and we all know the answer.

Phil spent his 20s in the newsroom of the Pensacola (Fla.) News Journal, his 30s on the road for AndroidCentral.com and Mobile Nations and is the Dad part of Modern Dad.