Good - Sleepwalking through the nightmare of Hitler’s Germany

The latest updates, reviews and unmissable series to watch and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

ONCE A WEEK

What to Watch

Get all the latest TV news and movie reviews, streaming recommendations and exclusive interviews sent directly to your inbox each week in a newsletter put together by our experts just for you.

ONCE A WEEK

What to Watch Soapbox

Sign up to our new soap newsletter to get all the latest news, spoilers and gossip from the biggest US soaps sent straight to your inbox… so you never miss a moment of the drama!

We would all have been heroes had we lived in Hitler’s Germany, wouldn’t we? We would have recognised the dangers of Nazism from the start, held fast to our moral principles and taken an unwavering stand against evil. Of course, we would. Not a doubt.

Well, some in the 1930s did have the prescience and courage, and some today would share their qualities, but there’s a chance that even more of us might actually be closer in thought and deed to Viggo Mortensen’s protagonist in Good, the long-gestated film based on British playwright C P Taylor’s acclaimed 1981 play.

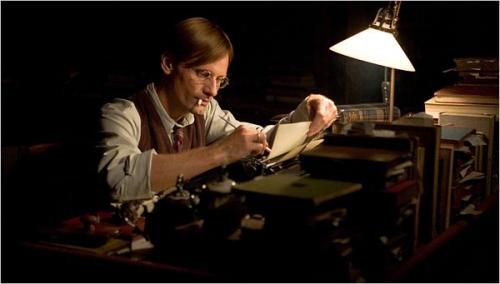

Mortensen’s John Halder is a respected professor of literature at a German university in the 1930s. He is enlightened, liberal, a ‘good’ man. Naturally, he has his flaws. He lacks 20/20 foresight, for a start. (“Hitler’s a joke,” he says in 1933 to his Jewish best friend, Jason Isaacs’ womanising psychoanalyst. “He’ll never last.”)

And he is too weak-willed to resist the seductive allure of one of his young students, Jodie Whittaker’s blonde, Aryan goddess Anne, for whom he leaves his eccentric wife (Anastasia Hille) and the muddle of their chaotically run home.

More crucially, he lacks the strength of character to say no when Hitler’s private secretary, Philipp Bouhler (played with forceful self-assurance by Mark Strong) invites him to join the Nazi party, having come across a book Halder once wrote tackling the issue of euthanasia, a novel inspired by his struggles to care for his senile mother (Gemma Jones).

Almost imperceptibly, Halder’s flaws of character and moral compromises take him, one small step at a time, deeper and deeper into the Nazi fold until he belatedly awakes from his sleepwalking to discover that he has become complicit with evil.

Like its central character, Good has its flaws. Though it has been sensitively adapted by John Wrathall and sympathetically directed by Brazilian filmmaker Vicente Amorim, Taylor’s play hasn’t made the transition from stage to screen entirely successfully. What works in the theatre doesn’t always work on film and the story’s episodic structure, revolving around key incidents in 1933, 1937, 1938 and 1942, does at times become rather plodding.

The latest updates, reviews and unmissable series to watch and more!

But Mortensen delivers an impressively nuanced performance, subtly conveying the way in which Halder’s outward rise in success and confidence is accompanied by an inner decline.

And even if Good isn’t great, it remains a chilling cautionary tale.

Would we behave better than Halder today? Maybe. All the same, let’s hope we’re not put to the test.

General release from 17th April

A film critic for over 25 years, Jason admits the job can occasionally be glamorous – sitting on a film festival jury in Portugal; hanging out with Baz Luhrmann at the Chateau Marmont; chatting with Sigourney Weaver about The Archers – but he mostly spends his time in darkened rooms watching films. He’s also written theatre and opera reviews, two guide books on Rome, and competed in a race for Yachting World, whose great wheeze it was to send a seasick film critic to write about his time on the ocean waves. But Jason is happiest on dry land with a classic screwball comedy or Hitchcock thriller.