What to Watch Verdict

Time skillfully examines the time lost by the families of those incarcerated in the prison system.

Pros

- +

🕓Thoughtful examination of the personal toll of having a family member in prison.

- +

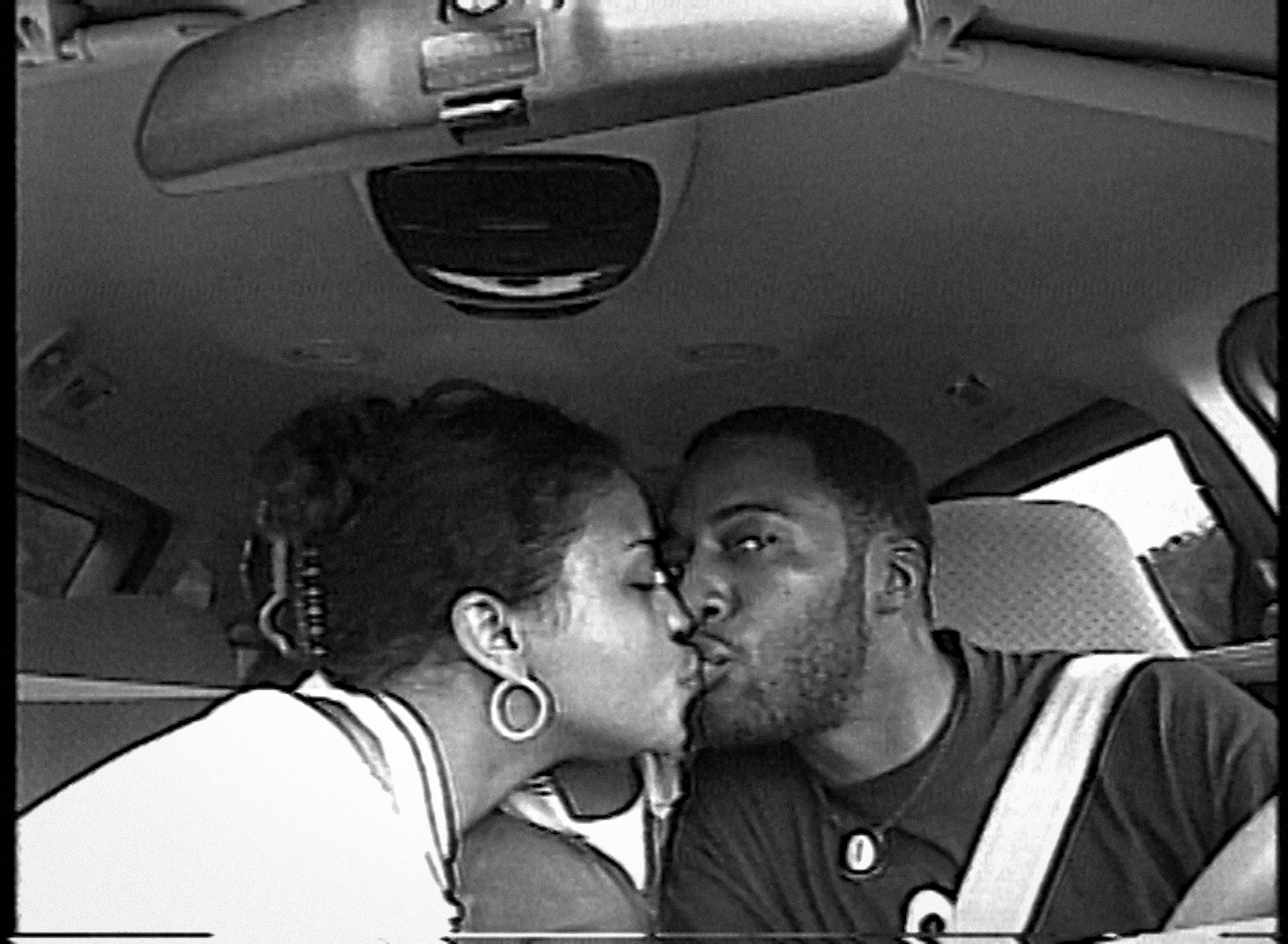

🕓Gorgeous black and white cinematography.

Cons

- -

🕓The home movies can be slightly overused.

When most people think of documentaries, they latch on to this idea that true stories hold educational value, that we’re meant to learn something from the real people and real situations that are being documented for our edification. Time isn’t that kind of movie. Director Garrett Bradley doesn’t need to educate you on how the criminal justice system works. She isn’t interested in laying out the political nature of Black imprisonment at increased rates for longer sentences, nor is she telling a story about systemic change. To some extent, that foreknowledge and moral certitude is assumed on behalf of the audience, who likely wouldn’t seek out a documentary relevant to prisoners’ rights without at least being sympathetic.

Instead, Time is a deeply personal film, chronicling the years one family spent without its husband and father and showing the impact that incarceration has on the individuals who live with its reality daily on the "free" side of the bars. Sibil Fox Richardson, affectionately known as “Rich,” was arrested with her husband Rob in 1999 after they participated in an armed bank robbery. Rich accepted a plea deal and served three and a half years in prison, leaving her young son and newborn twins with her mother. Rob, meanwhile, was sentenced to sixty years in prison, and the thrust of Rich’s life for eighteen years was to secure her husband’s release from that extreme sentence.

The film is shot in stark black and white, treating Rob’s absence like an absence of color in the lives of the Richardsons. Rich romantically remembers marrying her high school sweetheart and their shared dream of opening a hip hop clothing store, only to spend the next two decades raising her kids without their father. Rich never denies her or Rob’s involvement with the robbery, because their guilt is not the issue. Rather, it's the disproportionate impact their one decision had on their lives because imprisonment prioritizes punishment over rehabilitation of people and their communities, particularly when it comes to people of color.

Time effectively has two interweaving narrative conceits, split between Rich’s fight to free her husband in the present day and home video footage that emphasizes the gaps left in her sons’ lives by having their father taken from them. Reportedly, this documentary was meant to be a short film until Rich gave Garrett Bradley access to this wealth of home movies, and one is left to wonder whether it could have benefitted from still avoiding feature status. The home movies are touching and heartbreaking, contextualized as frozen moments of lost time that Rob and his family will never get to relive as a cohesive whole, but they also belabor the point without added weight. The point is served well enough with modern footage of their sons achieving greatness through graduations and student council debates without their father's supportive presence, and though the home movies offer perspective on those achievements through Rob’s absence, their extended runtime is sometimes a boon to telling the story of Rich’s fight for justice.

Rich’s evolution into prison abolitionist is not the sole point of the film, but it is the most interesting thread Garrett has to offer. Hearing Rich speak hopefully of making a New Year’s resolution every year to get her husband out of prison, only for the years to pass by and still have to make that resolution again and again, is nothing short of devastating. She never set out to be a public speaker or an expert on navigating courtroom bureaucracy, but it’s a necessity that radically transformed her for two decades so that she could have the tools to reunite with her husband. Nowhere is this pain more obvious than when, after days of politely calling the court about the state of her husband’s appeal, only to be repeatedly told that the orders have not been processed yet, she hangs up the phone and lets her collected strength crack into unrestrained rage. Her husband’s humanity is not important to the court that holds his freedom in its hands, and the way Garrett captures that lack of empathy by simply recording Rich’s half of the conversation is devastating in its simplicity.

Time isn’t about to change anyone’s mind about the inhumanity of the prison industrial complex. It takes that as a given and assumes you have enough sympathy to recognize that as an institutional failing of the United States. This is a story of humanity, of lives radically transformed by that system until they have nothing left but to spend their lives fighting it. Rob’s imprisonment left a temporal void in his family’s life that can never be taken back, but Rich’s fight is just as much about hope for the future as it is rectifying the wrongs of the past. What Time does best is remind us of how real the present is, divorced from statistics and knowledge of institutional prejudice. It reminds us that this injustice happens to people, and their lives aren’t abstract; they’re just as real as the ticking seconds we never get back.

Time is available to stream on Prime Video.

The latest updates, reviews and unmissable series to watch and more!

Leigh Monson has been a professional film critic and writer for six years, with bylines at Birth.Movies.Death., SlashFilm and Polygon. Attorney by day, cinephile by night and delicious snack by mid-afternoon, Leigh loves queer cinema and deconstructing genre tropes. If you like insights into recent films and love stupid puns, you can follow them on Twitter.