Pete's Peek | 'Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned' - Pasolini's Medea is a timeless visual triumph

The latest updates, reviews and unmissable series to watch and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

ONCE A WEEK

What to Watch

Get all the latest TV news and movie reviews, streaming recommendations and exclusive interviews sent directly to your inbox each week in a newsletter put together by our experts just for you.

ONCE A WEEK

What to Watch Soapbox

Sign up to our new soap newsletter to get all the latest news, spoilers and gossip from the biggest US soaps sent straight to your inbox… so you never miss a moment of the drama!

The cinema of Italian director Pier Paolo Pasolini is not to everyone’s taste, being a dense fusion of the poetic, the political and the polemic. While the dozen features the Marxist and avowed atheist made between 1961 and 1975 might only be screened to film students today, they were groundbreaking cinematic events on their release. Especially so the neo-realist masterpieces Accattone, Mamma Roma and The Gospel According to St Matthew; the Trilogy of Life series, a rich visual tapestry comprising the literary classics The Decameron, The Canterbury Tales and Arabian Nights; and the extremely graphic political satire Salo, which remains one of cinema's most controversial releases.

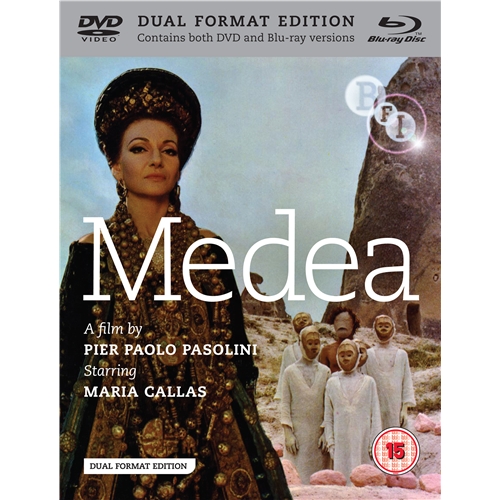

Pasolini also dipped his artistic pen into the myths of ancient Greece with two inspired adaptations, Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex in 1967, starring Franco Citti, and Euripides’ Medea in 1969, starring opera legend Maria Callas, which is being released by the BFI in a Dual Format Edition on 5 December.

In essence, Medea is the classic story of Jason and the Golden Fleece, but far removed from the 1960s Ray Harryhausen fantasy adventure that will be familiar to most film fans. This is Euripides’ original play brought to visceral life and the central theme here is ‘Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned’.

The woman in question is Medea (as played by Callas, in her only film role). Jason (played by Olympic champion Giuseppe Gentile) is bit of a bastard in this retelling. He comes from the modern world of Greece, while Medea belongs to more ancient ways. After helping Jason steal the fleece from her own people, Medea follows him to Corinth, but soon feels isolated and neglected. When Jason leaves her to marry the king’s daughter, Medea uses a most precious weapon to wreak revenge – Jason’s two sons (Note to self: Beware any woman bearing an oleander garland).

[nggallery id=534]

By shooting in a documentary-like style, with real locations and local people filling the screen, Pasolini imbues Euripides’ tragedy with a naturalistic streak. Here, the landscape is as important a character as Callas is as Medea. It’s one of the reasons why I have always been drawn to Pasolini’s films and documentaries (especially his UNESCO short La mura di Sana). In Medea, the chimney-like rock formations of Göreme in Cappadocia, Turkey stand in for the pagan world of Clochis; while the historic Piazza dei Miracoli at Pisa in Italy becomes modern Corinth. It's a perfect fit, representing the clash of cultures that permeates the story.

Medea is also practically wordless, with a soundtrack of mainly North African ethnic sounds. But the visuals are so magical, as is Callas’ carefully observed performance (she fills the screen in lots of close-ups) that you forget there’s hardly any dialogue and end up enjoying the film as a wonderfully hypnotic visual experience.

The latest updates, reviews and unmissable series to watch and more!

Released 5 December through BFI http://youtube.com/v/R0qIARHePv8