What to Watch Verdict

Darius Marder's story about a musician dealing with a career-derailing (and life-changing) disability offers a compassionate and relatable look at grace in the face of change.

Pros

- +

🥁 Marder captures the sensation of Ruben's deafness with both an emotional immediacy and powerful visceral cues.

- +

🥁 Ahmed's performance as Ruben captures the character's sometimes seemingly impossible journey with a tenderness that avoids melodrama.

Cons

- -

🥁 Less a criticism than something just to be aware of, but the filmmakers opt for obligatory English subtitles over the entire film.

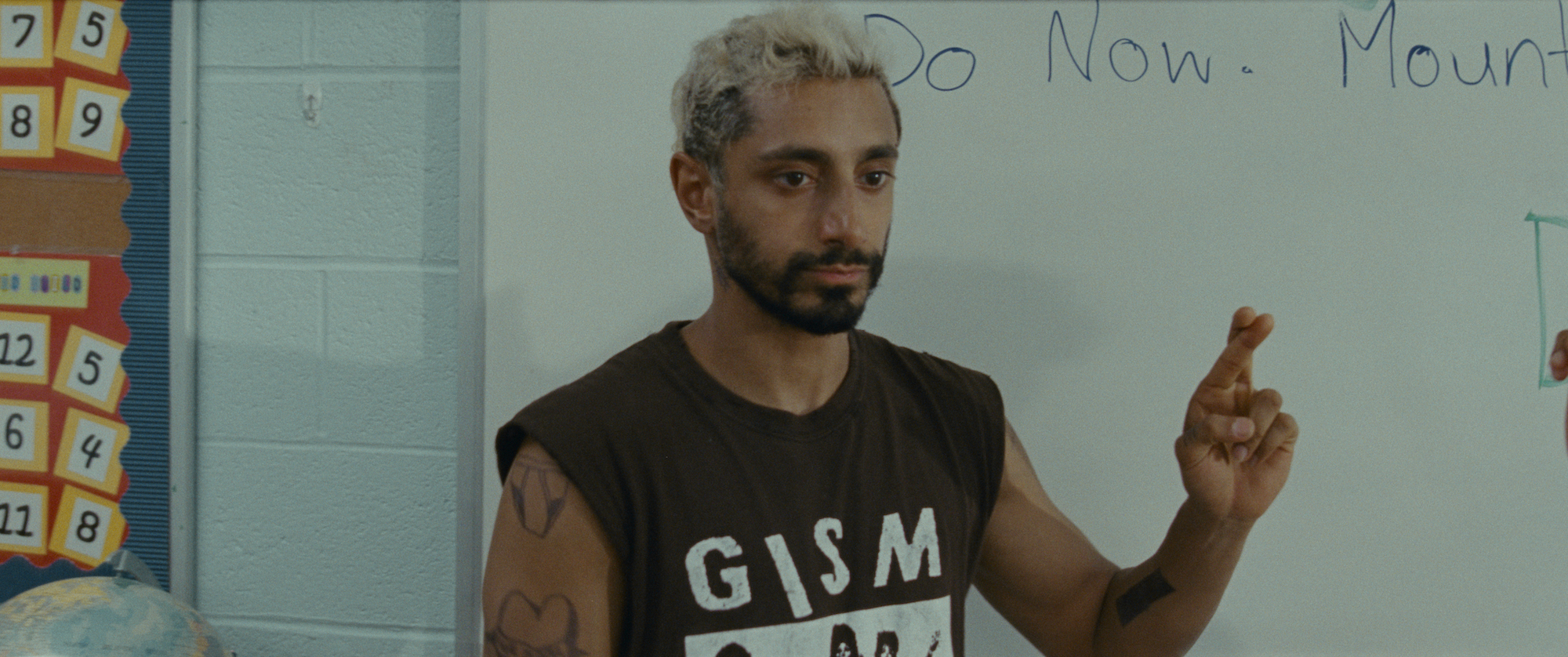

You wouldn’t expect a movie about a rock drummer to be quite so quiet, but Sound of Metal zigs every time you think it’s going to zag. The story of a musician who develops severe hearing loss, Darius Marder’s feature debut offers an extraordinarily thoughtful, sensitive look at a life-disrupting scenario, and the grace and resilience it takes to survive it. Bolstered by an amazing, understated performance by Riz Ahmed, Sound of Metal skillfully avoids phony melodrama in order to tap into some essential human truths, and is one of the year’s very best films.

Ahmed plays Ruben, half of the heavy metal duo Blackgammon: he’s the drummer backing up front-woman (and his girlfriend) Lou (Olivia Cooke). Not far into their latest tour, Ruben discovers that his hearing may be failing; a doctor’s visit confirms his worst fears, but offers a glimmer of hope — there’s a surgical procedure that might restore it, but it’s prohibitively expensive and isn’t covered by insurance. As he reels from the news, Lulu fears that he will relapse into drug use after four years of sobriety, and urges him to seek help before he succumbs. His sponsor guides him to a halfway house run by Joe (Paul Raci), a deaf, alcoholic veteran who helps people like Ruben dealing with both disability and addiction, but who insists he sever all contact from the outside world until he starts to reckon with his anger and anxiety about losing his hearing.

Ruben complies only reluctantly at first as Joe urges him to accept his situation and learn how to live as a deaf person. Before long, Ruben develops friendships within the insular community and begins to let go of those painful feelings that keep him tethered to the past — including a past that involves drug abuse. But after deciding to sell all of his belongings, including their musical equipment and the trailer they drove on tour, to raise money for the operation to restore his hearing, Ruben is forced to a crossroads where he can either accept being deaf or continue to pursue his dreams of hearing and playing music, without any guarantees that his life can resume just as before even if the surgery succeeds.

Ruben’s plight reminds viewers of stories about star athletes whose careers were sidelined by injury — the shock of the loss gives way to reluctant acceptance not only that they won’t be able to pursue their dreams, but may not even be able to function normally — meaning as they always had before then — ever again. Even without aspirations to be a musician, it seems unimaginable to consider the possibility of never hearing music (or anything else) ever again. Appropriately, director and co-screenwriter Darius Marder explores Ruben’s future with understanding and compassion, spotlighting stages of grief without judging him, and more importantly, forcing each moment in that journey to the next one. There would undoubtedly be moments where Ruben would fixate on the hopeful, possibly delusional solution, and others where his rage was all consuming; Marder and his co-writer, brother Abraham, validate each of these feelings without the need for falsifying conflict or amplifying it with melodrama.

Particularly in a year where audiences are themselves experiencing so much loss, be it financial, social, or personal, Sound of Metal reverberates particularly loudly, because at its heart the film is less about Ruben’s specific disability than the ability to accept and come to terms with change that we cannot control. At the beginning of the film, Ruben has regained control of his life after an already devastating setback — repeated drug abuse — and achieved a modest but significant measure of success as a musician with the woman he is very much in love with. That gets taken away from him and he must learn how to cope, and as he moves into the deaf community Joe runs, must learn to accept the restrictions imposed, especially those that he doesn’t agree with even if they are supposed to be for his own good. Joe’s ultimate lesson becomes one more deeply profound than “accept the silence,” and it takes Ruben a long time to understand that, much less actually accept it, and then it becomes the lesson we need to learn as well.

To create the immediacy of Ruben’s situation, meanwhile, Marder and sound designer (and co-composer) Nicolas Becker design a complex, deliberately disorienting but extremely intimate sense of what it’s like to be inside the character’s head — first the sensation when he loses his hearing, and then as he begins to re-engage with the world from the point of view of a deaf person. The soundtrack forces viewers to lean in and pay a different kind of attention, not just following the story but truly experiencing moments feeling both the emotional sensation and the visceral as he misses exchanges, feels alienated, and loses this fundamental element of his communication with everyone else. And again, Marder astutely observes that it’s not angelic choirs that Ruben is missing, it’s the whirr of his smoothie blender and the low roar of planes flying overhead, things taken for granted that orient us in our space and give a sense of continuity and comfort.

Ahmed continues to be a thrilling chameleon to watch on screen — no performance of his feels like another — but what Sound of Metal highlights is that what could or should be a showcase for him never feels like an opportunity to show off. His Ruben is restless but disciplined, distraught and angry about his circumstances but direct and mostly courteous to the people around him. (I’ve seldom better been able to relate to a character than a scene where he smashes a doughnut in rage but keeps repairing it, then smashing again.) It’s truly an extraordinary performance, and one easy to get inside as a viewer. As Lou, Cooke manages to avoid the dangers of playing a wan artist whose troubles define her like Ruben’s might define him, giving her a compassionate, frightened edge that leads her away from him as he goes on a journey that he needs to take alone.

The latest updates, reviews and unmissable series to watch and more!

As Joe, Paul Raci becomes the film’s quiet conscience, offering simple wisdom that he knows it would be foolhardy to explain further to Ruben until the young man can understand it for himself. He’s astonishing in a wonderfully ordinary way that, sure, provides a sort of expository voice for each development in Ruben’s journey, but expresses a level of compassion that encourages the audience to follow as well. Meanwhile, Mathieu Amalric (The Diving Bell and the Butterfly) appears as Lou’s estranged father, a kinda-sorta Serge Gainsbourg type — even singing with his daughter at one point — lending a similarly human edge to a character whose introduction in a lesser story might serve only to divide and cause drama.

Ultimately, the surprising honesty of even these largely functional characters is emblematic of the film as a whole; Marder seems to realize that there’s enough tension in Ruben’s very reasonable, relatable choices to create drama, without relying on arch confrontations, falsely-undertaken risks, or other “developments.” And it’s precisely the understatedness of this approach that makes Sound of Metal work so powerfully: It’s not another challenge on the horizon that keeps us fighting, but the quiet and calm that envelops us after the last one that allows us to move towards the next. Where it would be easy for Ruben to lash out, to explode, self-destruct, it’s his trying in spite of his feverish false hopes, his struggles, setbacks and feeble successes, but most of all his clear-eyed view at the path in front of him — his acceptance — that enables his journey to resonate, transcend, and perhaps unexpectedly, to teach.

Todd Gilchrist is a Los Angeles-based film critic and entertainment journalist with more than 20 years’ experience for dozens of print and online outlets, including Variety, The Hollywood Reporter, Entertainment Weekly and Fangoria. An obsessive soundtrack collector, sneaker aficionado and member of the Los Angeles Film Critics Association, Todd currently lives in Silverlake, California with his amazing wife Julie, two cats Beatrix and Biscuit, and several thousand books, vinyl records and Blu-rays.