The Lady - Aung San Suu Kyi: orchids in her hair and iron in her will

The latest updates, reviews and unmissable series to watch and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

ONCE A WEEK

What to Watch

Get all the latest TV news and movie reviews, streaming recommendations and exclusive interviews sent directly to your inbox each week in a newsletter put together by our experts just for you.

ONCE A WEEK

What to Watch Soapbox

Sign up to our new soap newsletter to get all the latest news, spoilers and gossip from the biggest US soaps sent straight to your inbox… so you never miss a moment of the drama!

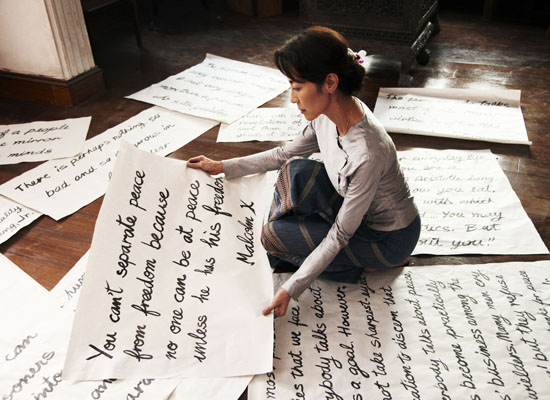

A physically slight woman with a core of steel; a thorn in the side of authority; an implacable opponent of male violence: no, this is not a description of Stieg Larsson’s fantasy tattooed girl but of a heroine living in the real world - Burmese peace campaigner Aung San Suu Kyi, the inspirational subject of Luc Besson’s biopic The Lady.

As a filmmaker, Besson is no stranger to strong women, but they’re usually kick-ass chicks toting guns (witness 1990’s Nikita, 2011’s Colombiana, and umpteen other examples in between). Not an image one associates with demure pacifist Aung San Suu Kyi. For The Lady, however, Besson is on his best behaviour, but he’s so buttoned-up that his film is a little dull, his directorial restraint matched by Rebecca Frayn’s worthy but pedestrian script.

Even imperfectly told, however, Aung San Suu Kyi’s story remains astonishingly powerful and moving. For more than two decades she has been a beacon of hope for the Burmese people, despite spending almost all of that time in one form of a detention or another, a victim of the country’s military dictatorship.

Yet as Besson’s film shows, her political role came about largely by accident. In 1988, the year her life changed, she was living quietly in Oxford as the wife of academic Michael Aris and mother of two sons. Then she returned to Burma to care for her dying mother, the widow of General Aung San, hero of Burma’s independence struggle, who had been assassinated in 1947, when Aung San Suu Kyi was two years old.

Arriving in Burma she found herself in the midst of a brutal crackdown by the military junta against the country’s student-led protest movement. As her father’s daughter, Aung San Suu Kyi was thrust into leading the revolt against the regime, addressing half a million people at the Schwedagon pagoda in Rangoon only a few months after her return. In 1990 she led Burma’s National League for Democracy to a landslide victory in elections that were promptly ignored by the military. Inspired by the example of Gandhi, she remained unwavering in her commitment to non-violent resistance.

As the film shows, this came at great personal cost. Kept under house arrest for 15 years, notwithstanding the award of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991, she endured enforced separation from her husband and children. When her husband was dying of cancer in 1999, she didn’t dare travel to England to be with him for fear the junta would prevent her ever returning to Burma. When she was finally released from house arrest in November 2010, she hadn’t seen her sons for 10 years.

It’s an astonishing story of moral and physical courage, and these qualities come across vividly in The Lady, for all its flaws. In the film’s leading role, Michelle Yeoh conveys Aung San Suu Kyi’s grace and dignity, even if she doesn’t sound particularly like her (unlike Meryl Streep’s Iron Lady, Yeoh’s Lady isn’t an impersonation). As her Oxford don husband, David Thewlis is warm, sympathetic and slightly shambling, while offering glimpses of the inner strength that enabled Aris to support his wife unstintingly, even through his terminal illness.

The latest updates, reviews and unmissable series to watch and more!

In the end, it doesn’t matter that Yeoh and Thewlis’s dialogue is sometimes stilted. Aung San Suu Kyi’s charisma couldn’t be stifled by the Burmese military and the odd duff line can’t dent it here. Besides, the film’s most affecting moments are wordless – as when Aung San Suu Kyi refuses to be deterred by a line of gun-wielding soldiers as she leads a group of protesters. Even when a jittery officer brandishes his weapon in her face, she refuses to back down. A slender woman refusing to be cowed by aggression is a potent symbol, as Burma’s repressive rulers know all too well. Forget fantasy figures like Lisbeth Salander. Aung San Suu Kyi is a true heroine for our times.

On general release from Friday 30th December 2011.

A film critic for over 25 years, Jason admits the job can occasionally be glamorous – sitting on a film festival jury in Portugal; hanging out with Baz Luhrmann at the Chateau Marmont; chatting with Sigourney Weaver about The Archers – but he mostly spends his time in darkened rooms watching films. He’s also written theatre and opera reviews, two guide books on Rome, and competed in a race for Yachting World, whose great wheeze it was to send a seasick film critic to write about his time on the ocean waves. But Jason is happiest on dry land with a classic screwball comedy or Hitchcock thriller.