'Ammonite' sacrifices women's contributions to history in favor of a fictional love story

The drama Ammonite chooses to fictionalize a romance between two real-life women rather than portray their historical achievements.

The latest updates, reviews and unmissable series to watch and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

ONCE A WEEK

What to Watch

Get all the latest TV news and movie reviews, streaming recommendations and exclusive interviews sent directly to your inbox each week in a newsletter put together by our experts just for you.

ONCE A WEEK

What to Watch Soapbox

Sign up to our new soap newsletter to get all the latest news, spoilers and gossip from the biggest US soaps sent straight to your inbox… so you never miss a moment of the drama!

This post contains mild spoilers for Ammonite.

In an awards season of ambiguity and pandemic-induced change, there are few films that carry the weight of seeming Oscar guarantees. One such title is Ammonite, the historical romance written and directed by Francis Lee. Kate Winslet plays Mary Anning, a real-life paleontologist barely surviving by selling fossils and painted seashells as tourist trinkets while caring for her ailing elderly mother. The days of her most celebrated professional discoveries are behind her and the male-dominated upper-class world of historical academia has rejected her. In desperate need of funds, she finds herself unable to reject the offer of Roderick Murchison, a wealthy baronet and wannabe geologist. After allowing him to stumble alongside her on a minor expedition, he asks her to look after his young wife Charlotte, who is struggling with grief and melancholy. Initially, the two women are divided in almost every way: by age, class, personality, and occupation. Soon, however, Charlotte comes out of her shell and the two women's bond grows into a passionate romantic affair. It's a great story. It's also not true.

There's no historical proof that Mary Anning and Charlotte Murchison had a sexual relationship, although Anning's own sexuality has been the subject of speculation. Murchison was also eleven years older than Anning. Of course, it’s hardly uncommon for a film to take liberties with fact to create its own narrative or use real-life figures to explore various themes. Peter Shaffer and Milos Forman did it with Amadeus, using two beloved composers as mouth pieces for ideas of death, legacy, and artistic devotion. Phillip Kaufman’s 2000 drama Quills reimagines the final days of the life of the Marquis de Sade as a baroque battle between church and state and rallying cry against censorship and sexual oppression. Even Hamilton eschews mere concepts of realism to better illustrate the story of America's founding days as a truly inclusive one that better relates to modern audiences. There is reason behind this approach, and it’s there with Ammonite. The romantic aspects are appealing, in large part thanks to the chemistry of the leads, and Lee strongly conveys the all-consuming allure of finding a like-minded soul after years of forced solitude. LGBTQ+ history is also dishearteningly full of gaps, and stories like this help us to remember that centuries of change were not solely dictated by cishet white men in cravats.

There is nothing unusual or especially egregious about Lee’s creative choices. Anning and Murchison are little-known figures and appropriating them in such a manner was never likely to cause the same controversy as, say, the re-writing of Freddie Mercury’s AIDS diagnosis in Bohemian Rhapsody. This happens all the time in art, and the final product of Ammonite is one that has resonated with many LGBTQ+ viewers. Yet I, a bisexual woman myself, cannot shake the memory of what could have been with this story had Lee stuck more closely to the true lives and contributions of Anning and Murchison.

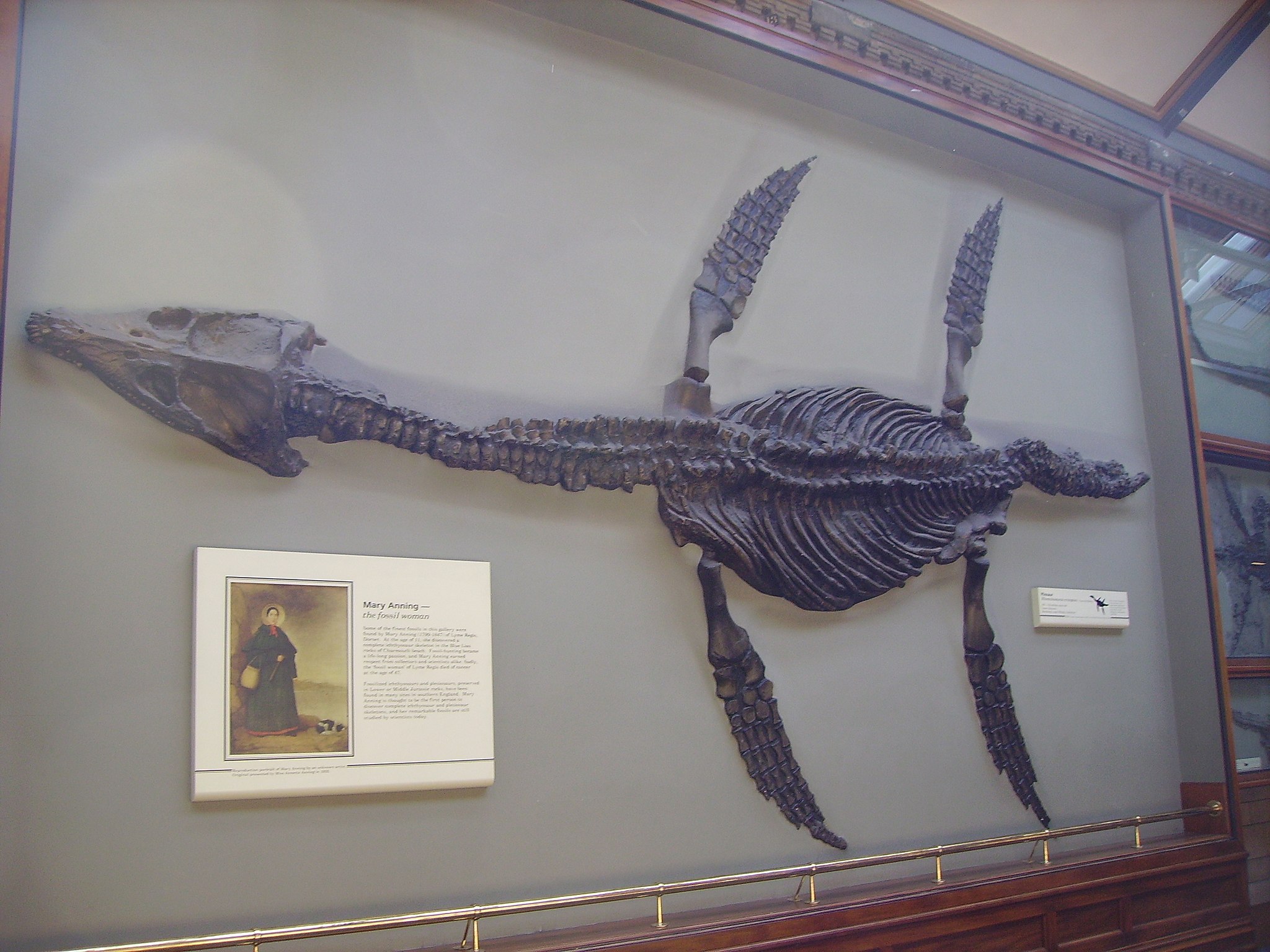

Mary Anning is one of the defining figures in British palaeontological history. Her discoveries included the first correctly identified ichthyosaur skeleton and in the correct identification that coprolites, known as bezoar stones, were fossilized feces. Despite her efforts and the indelible impact she had on the field, she was consistently forced out of the scientific community and, as a woman, was never able to join the Geological Society of London. Much of her work went unaccredited in her lifetime, a detail that is noted in the opening of Ammonite. Her life and discoveries are both deeply fascinating and dishearteningly indicative of how women were smudged out of history by inferior men.

Charlotte Murchison did stay with Anning for several week, after she and her husband decided that she should stay in Lyme and work to "become a good practical fossilist." Murchison built her own important fossil collections and, alongside her husband, contributed greatly to the field. She created geological sketches of important features, worked to develop much of Roderick's written work, and defied convention at the time by attending geological lectures at King's College, London, even though the professor, Charles Lyell, refused to admit women. The scientist and writer Mary Somerville wrote glowingly of Charlotte in her own memoirs, describing her as "an amiable accomplished woman, [who] drew prettily and - what was rare at the time - she had studied science, especially geology, and it was chiefly owing to her example that her husband turned his mind to those pursuits in which he afterwards obtained such distinction."

It's rare that the historical achievements of women are given their dues in pop culture, even more so when done as part of a loving and fulfilling collaborative effort with their spouse (Radioactive, the recent biopic on Marie and Pierre Curie, is a recent exception.) Perhaps Lee didn’t think that a story of two women bound by both isolation and a shared academic passion, strengthened in the face of misogyny, wouldn’t appeal to broader audiences. It is pretty hard to get general viewers interested in fossilized poop and the agonizingly slow process of cleaning bones of residue. Still, even as it keenly portrays this dynamic of desperate loneliness, these fictionalized elements of love overpower the historical truth in a way that feels oddly lacking. The decision to prioritize a made-up romance over the tangibly real contributions both women made to the world is reductive to both of their legacies. As appealing as the romance is, it ends up being a lot less remarkable than these women were in their time.

The latest updates, reviews and unmissable series to watch and more!

It’s a shame because Ammonite succeeds in many ways: as a handsomely made story of repression, isolation, and forced silence in the face of a cruel world, it has much to offer. Yet it ends up doing the very same thing it critiques by smudging away the achievements of two brilliant women in favor of something that wasn’t true but would prove juicier to modern audiences. You leave the movie desperate to know more about the work of Mary Anning and Charlotte Murchison. Fortunately, there are plenty of resources available, but it remains a disappointment that the most high-profile narrative both women will ever receive in the popular consciousness didn’t seem to care about such things.

You can read our full Ammonite review here.

Kayleigh is a pop culture writer and critic based in Dundee, Scotland. Her work can be found on Pajiba, IGN, Uproxx, RogerEbert.com, SlashFilm, and WhatToWatch, among other places. She's also the creator of the newsletter The Gossip Reading Club.