Gran Torino

The latest updates, reviews and unmissable series to watch and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

ONCE A WEEK

What to Watch

Get all the latest TV news and movie reviews, streaming recommendations and exclusive interviews sent directly to your inbox each week in a newsletter put together by our experts just for you.

ONCE A WEEK

What to Watch Soapbox

Sign up to our new soap newsletter to get all the latest news, spoilers and gossip from the biggest US soaps sent straight to your inbox… so you never miss a moment of the drama!

“Get off my lawn.”

Nah, doesn’t have quite the same ring as “Go ahead, make my day”, does it? This, though, is what the 78-year-old Clint Eastwood is reduced to snarling in his latest movie as star and director, Gran Torino. Yes, the abiding demand of old codgers everywhere: “Get off my lawn.” Has it really come to this for the great icon of American masculinity?

It appears so. Gran Torino is reportedly Eastwood’s final acting role, so his portrayal of the film’s aged widower Walt Kowalski cannot help but appear as a last wheezing gasp for the type of tough guy he has embodied for most of his career, a farewell to Dirty Harry and all his kind.

All of which makes what the movie has to say – about Eastwood’s screen image and about contemporary America - even more fascinating.

Gran Torino’s Walt is a blue-collar bigot. A veteran of the Korean War who spent 50 years working on the line in a Detroit Ford auto plant, he is completely out of step with the times. His dismay at the changed world around him is clear from the start of the movie, which finds him in the process of burying his wife after a lifetime together.

He has no affinity with his middle-aged yuppie sons (they drive foreign cars, for heaven’s sake), his disrespectful, midriff-baring, mobile-using grandchildren appal him, and he has nothing but disdain for the young priest (a “27-year-old over-educated virgin”) who wants to honour a promise he made to Walt’s late wife and get Walt to attend confession.

As for the once all-white neighbourhood where he has lived for years, don't get him started. He’s full of contempt for the Asian immigrants he now lives among, spitting out a stream of racial slurs that would make Alf Garnett or Al Murray (or Archie Bunker, to give an American example that Walt would recognise) seem beacons of tolerance.

The latest updates, reviews and unmissable series to watch and more!

You’d reckon Walt would be way too old to change his ways, but change he does after he is grudgingly drawn into the lives of the Hmong family living next door. (It’s one of the many ironies that the movie throws up that Hmong people, who come from Laos and other parts of Southeast Asia, only immigrated to the States in large numbers because they sided with the US during the Vietnam War and consequently faced retribution after the conflict.)

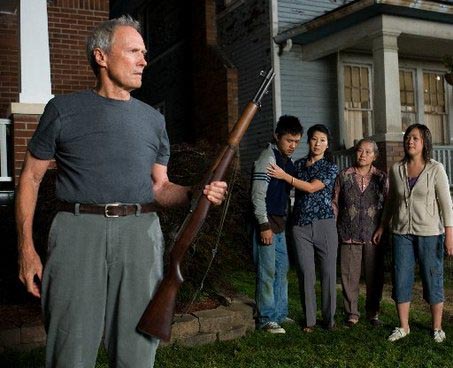

Walt only begins to have any contact with his neighbours after he catches shy 16-year-old fatherless boy Thao (Bee Vang) trying, as part of an initiation rite to join a local Hmong gang, to steal Walt's treasured 1972 Gran Torino car. Even then, he wants nothing to do with Thao and his family, but thanks to the insistence of Thao’s older sister, Sue (Ahney Her), he gets the boy to do a series of small jobs around the neighbourhood as payback for his attempted crime.

Gradually, the old man and the boy begin to form a bond. And when Thao and Sue’s troubles with the local gangbangers get more serious, Walt steps in…

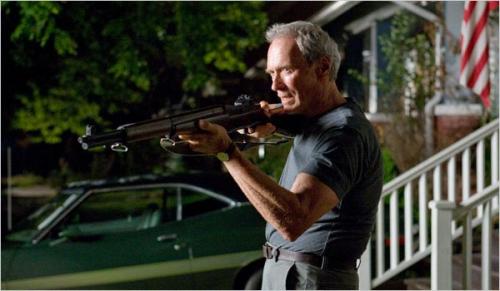

Is this a last hurrah for Dirty Harry?

No. In fact, the way that Gran Torino finally deals with the question of violence turns out to be a repudiation of Dirty Harry and all he stands for.

When Eastwood made Unforgiven the best part of two decades ago, the movie - in which an ex-gunfighter reluctantly returns to the way of the gun with grisly consequences - was widely seen as a corrective to the Westerns he had made in his career. But Unforgiven was ambivalent about violence and it was still possible, if you were so disposed, to cheer legendary gunman Clint’s fearsome prowess.

Gran Torino goes much further, however, towards a rejection of violence as a solution, though you’ll need to see the movie to find out how.

It’s well worth the trip to the cinema. True, the film is clunky in places, and the acting (not least by Clint himself, it has to be said) sometimes strikes bum notes. But it is also warm, funny and moving, and genuinely thought-provoking about no end of hot-button contemporary issues, from race and class, to ageing and masculinity. Eastwood may be saying goodbye to acting, but on this basis he isn’t so out of touch after all.

(General release from 27th February)

A film critic for over 25 years, Jason admits the job can occasionally be glamorous – sitting on a film festival jury in Portugal; hanging out with Baz Luhrmann at the Chateau Marmont; chatting with Sigourney Weaver about The Archers – but he mostly spends his time in darkened rooms watching films. He’s also written theatre and opera reviews, two guide books on Rome, and competed in a race for Yachting World, whose great wheeze it was to send a seasick film critic to write about his time on the ocean waves. But Jason is happiest on dry land with a classic screwball comedy or Hitchcock thriller.